. Famous Places and Powerspots of Edo 江戸の名所 .

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

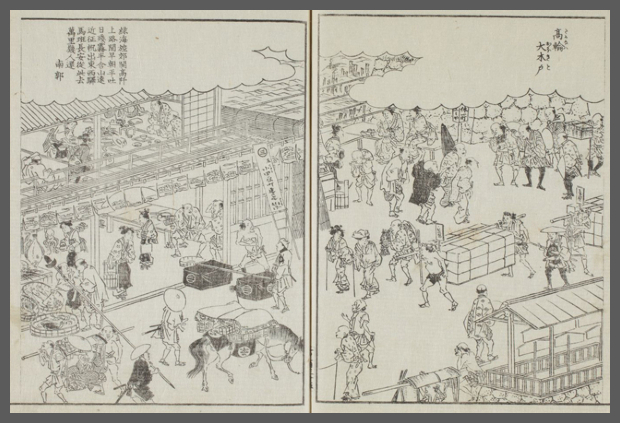

Tamagawa Joosui 多摩川上水 Tamagawa Josui Kanal

idohori shi 井戸堀師 digging a well

or making a new well

To provide clean water for the people of Edo was quite a job.

The wells were not dug in the ground but water from a river or public waterway (for example Tamagawa Josui 玉川上水) was let through wooden pipes (kidoi 木樋) to a huge well tank under ground, where the people could take it out for their daily use.

Drinking water was stored in each home for cooking.

Digging wells in the low-lying parts of Edo would only yield salty water from the sea.

In these parts water was transported by

mizubune 水舟 "water boats".

mizuya 水屋 water salesmen carried the water from the boats to the customers.

The whole system was supervised by the

mizubugyoo, mizu bugyō 水奉行 waterworks administrator

. Drinking water : cleaning wells and waterways .

歌川広重 Utagawa Hiroshige

. - The Waterways in Edo - .

Tonegawa 利根川 (Tone River) // Arakawa 荒川 // Tamagawa 多摩川 / 玉川 (Tama River) // Sagamigawa 相模川 (Sagami River)

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

- quote -

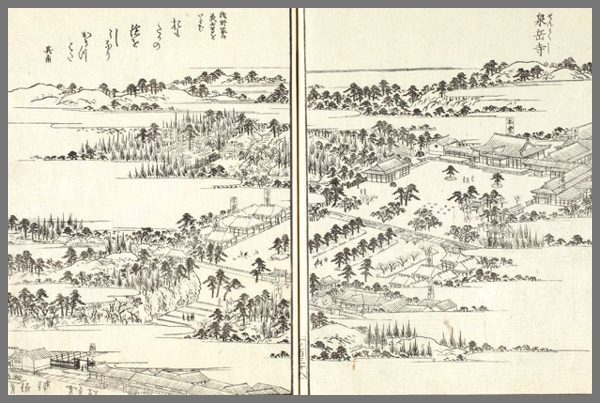

Mogusa-mura Shōren Zenji 百草村松連禅寺

Shoren-ji was first built during the Tempyō era (729 to 749), and was abandoned in the Kamakura period.

During the Kyōhō era (1716 to 1735), this temple was rebuilt by 大久保家 the Ōkubo Family, castellans of Odawara Castle,

to pay a tribute to the memory of 徳川信康Tokugawa Nobuyasu, the eldest son of Tokugawa Ieyasu.

百草園 Mogusa-en was a garden developed in this occasion.

In this garden, there was 松蓮庵 Shōren-an, a one-story house with a raftered roof, and

寿昌梅 Jushō-bai, an old plum tree with a large trunk, and both of them are known as symbols of Mogusa-en.

- source : Tokyo Metropolitan Library -

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

- quote

Tamagawa Josui - Edo's Water Supply

One of the busiest men in Edo is the mizu-bugyo (the water "mayor") -- the man in charge of Edo's water supply. It is a huge job to keep the water system in Edo working properly. Since all the pipes are made of wood, they need to be replaced once in a while. Earthquakes are not uncommon in Edo, and even a small quake may cause pipes to crack or start to leak. In times of drought, the supply of water needs to be carefully controlled, to make sure that it is distributed fairly to all parts of the city. The job of managing the city's water system is handled by the mizu-bugyo and a staff of mizu-bannin (water technicians).

The mizu-bugyo is one of the few top officials in the bakufu who is appointed to his position, rather than inheriting it. He and his assistants, the mizu-bannin, are responsible for handling all of the repair work on the banks of the canals, as well as maintaining the distribution systems through the city.

Before Tokugawa Ieyasu moved to Edo in 1590, the town was still very small, and the people living in Edo got all the water they needed from the small streams flowing down from the hills of the Yama-no-te into Edo Bay. The main streams were the Koishikawa (Koishi River) in the north, and the Megurogawa (Meguro River) in the south. When the Tokugawa family moved to Edo, with all of his warriors and retainers, it quickly became clear that the traditional sources of water would not be enough to supply all the people in the growing town. Therefore, Ieyasu started the first of many water supply projects, or josui , to bring water to the city. ("jo-sui" literally means "lifting water" or "water inflow")

The first thing Ieyasu did was to build an extensive network of wells throughout the city, which were supplied with water from the main streams -- mainly the Koishi River. Wooden sluices and pipes were built to carry water underground from the river to each of the wells. This ensured that people living in every part of the city had access to fresh water. However, it did not increase the supply. After Ieyasu became Shogun, in 1603, Edo started to grow even more rapidly, and soon there was not enough water to supply all of the wells in the city.

The second major josui project that the Tokugawa shoguns carried out was the Kanda josui . To increase the volume of water supplied to the city wells, two large canals were built to redirect the flow of several smaller streams. Before, they used to flow into the Tama river, but once the canals were built the water flowed straight through the center of Edo. This new man-made "river" was named the Kanda-gawa (Kanda River) because it joined up with the Koishi river at a point near Kanda.

The main branch of the Kanda river starts at a small lake, which was named "Inokashira" (the head of the well), because it supplies all of the wells in Edo. This lake is about ten kilometers west of the city. A smaller branch starts in an area of marshes near Zenpukuji temple, so it was named the Zenpukuji river. The Kanda josui runs east through the hilly Yamanote area until it reaches Yotsuya. At Yotsuya, the water flow is divided. Part of it enters the main outer moat surrounding Edo Castle, and the rest of the water is directed into the main pipes that supply water to all of the city's wells.

An important part of the Kanda josui water project was to build the underground piping system that would carry water from the main intake at Yotsuya to each of the wells in the city. It took a huge effort to dig the trenches, build wooden pipes to carry the water to the wells, and then rebury all the pipes under the city streets. By the time this project was complete, there were about 67 kilometers of underground pipes supplying water to over 3600 wells in the city. At one point, one of the main water pipes crosses back over the Kanda River on top of a large bridge. This bridge is named Suido-bashi, or "Water-works Bridge".

The Kanda josui and a few smaller canal projects were able to provide enough water for the city for several decades. But Edo continued to grow. By the mid-1600s the population was already well over half a million people, and once again there were water shortages as the current supply system was insufficient to meet the needs of all the people. The third Shogun, Iemitsu, realized that water shortages could soon cripple the economy of Edo, so he ordered the most ambitious water supply project yet; a canal to carry water from the Tama river -- 50 kilometers west of the city -- to downtown Edo.

Work began on the Tamagawa josui in February 1653. A small dam was built on the river near the town of Hamura, and workmen began digging a canal across the hills to carry the water to Edo. At that time, there were only a few small villages located in the hilly, wooded region between the northern suburbs of Edo and the Tama river. Apart from one or two small streams, there were few good sources of water in the area, and certainly not enough to support rice farming.

It was rough work digging the huge canal -- in some places, the workers had to dig a channel as much as 18 meters deep -- through the heavily wooded hills. However, as the digging work proceded, and the canal reached further and further towards the city, people began to move into the cleared areas where the workers built their camps, and soon small towns began to spring up along the banks of the canal. The Shogun assigned such a large group of workmen to the Tamagawa josui project that they were able to complete the canal in just seven months. Once the water began flowing through the canal, many areas to the west of the city were transformed from woodlands into small farming towns, which grow vegetables to sell in the city.

The Tamagawa josui links up with the Kanda josui just to the west of the city, and the underground piping system was redesigned and extended to cover an even wider area of the city. Today, there are more than 150 kilometers of pipes in the Edo water systems, and the wells that are connected to this water system supply over 60% of the citizens with water for drinking, bathing and washing.

However, there are still some parts of the city where it is impossible to build wells and waterworks, particularly in the low-lying areas along the coast of Edo Bay, in Fukagawa and Kiba. Whenever you dig a well, it quickly fills up with salty water. People who live in these areas cannot get their drinking water from the wells, although they do use well water for bathing and washing. Drinking water must be carried into these areas of the city in special boats called mizu-bune (water boats).

A large pipe from the main water system empties into the Nihonbashi River at a point near Edo Castle. The mizu-bune load up with water at this pipe, and then travel to the areas of the city that have no wells. Water salesmen, or "mizu-ya", meet the boats at one of the piers in this area, and fill large buckets with water. Then they walk from door to door carrying their water buckets and sell drinking water to the people who live there. Although this system is somewhat inconvenient, the cost is very low.

The water-sellers store water in large casks and tanks in each neighborhood, so the people who live in these areas can always find water nearby when they run out. The system of mizu-bune and mizu-ya is managed by the government. This system allows thousands of people to live in an area that would otherwise be almost uninhabitable.

- source : Edomatsu

- - - - - - - - - -

Catching Sweetfish in Tama River 玉川猟鮎(たまがわあゆりょう)

Tama River was famous for its sweetfish.

It is written that from early summer to late autumn,

the Edo residents would come to Tama River

from miles around to catch sweetfish.

. source - Tokyo Metropolitan Library .

- Related to the 神田上水 Kanda Josui

. Suidō 水道 Suido district .

in Bunkyo and Shinjuku.

. Kugayama 久我山 Kugayama district - Suginami .

ホタル祭り Hotaru firefly festival along the waterway

. Chōfu Tamagawa 調布玉川 Chofu .

.......................................................................

- quote -

Actor Immitating Summer Peddling (Haiyū Mitate Natsu Shōnin)

A Kabuki actor portrays one of the summer's popular businesses. In the picture is written the phrase, "Let's cool off the gut of (a pun also meaning 'to frighten') the luke-warm actor. Selling utsumaki-taki icewater." The picture depicts a merchant selling icewater.

Kanda and Tamagawa waterworks were built to supply daily drinking water to people in Edo. But the water tasted bad and they bought water from water merchants called "Botefuri" (merchant carrying water on a pole and selling it).

In addition to such water merchants, "botefuri" selling ice water appeared in summer. An essay called "Morisada mankō", written in the end of the Edo period, introduced ice water merchants selling ice water with dumpling made from rice flour and items with white sugar in it, which was a unique business in Edo, not seen in the Kansai area.

On June 1, there was a ceremony in which the Kaga domain presented the ice stored at the ice room in Komagome to the Shōgun. The spare ice was distributed to passersby. Cold water and ice water to beat the heat were one of seasonal traditions in summer in Edo. An actor in the picture is Ichikawa Uzaemon XII. The house of Ichikawa Uzaemon was a famous family as the manager of the theater, "Ichimura-za".

- source : Tokyo Metropolitan Library -

..............................................................................................................................................

Inokashira 井の頭 "Head of the Well"

Mitaka 三鷹市井の頭

- quote -

Inokashira Park (井の頭恩賜公園 Inokashira Onshi Kōen) straddles Musashino and Mitaka in western Tokyo, Japan. Inokashira Pond (井の頭池) and the Kanda River water source (神田上水 Kanda jōsui), established during the Edo period, are the primary sources of the Kanda River.

The land was given to Tokyo in 1913. On May 1, 1918, it opened under the name Inokashira Onshi Kōen (井の頭恩賜公園), which can be translated as, "Inokashira Imperial Grant Park". Thus the park was considered a gift from the Emperor to the general public.

- - - More in the WIKIPEDIA !

. Benzaiten Shrine at Inokashira in Snow .

Print by Hiroshige

. Kawase Hasui 川瀬巴水 (1883 - 1957) .

Night view of Benten Shrine Snow at Inokashira Park

The Inokashira Benten Shrine in Snow (Shatô no yuki)

- quote -

Inokashira Pond Benzaiten Shrine

井頭池 弁才天社 Inokashira Ike no Benzaiten no Yashiro

Inokashira Pond is the water source of Kanda Jōsui,

the first canal system developed during Edo times.

Benzaiten refers to the story that, during the Tengyō era (938-946),

源経基 Minamoto no Tsunemoto (?-961) first installed a statue of the goddess Benzaiten at the shrine.

The statue had been made by Dengyō Daishi (the priest who founded Tendai Buddhism).

During Edo times, the shrine attracted the religious fervor of those

who were born and raised in the city.

Furthermore, in that the area surrounding the shrine was very fertile;

many trees were planted in order to cultivate the water source.

- source : Tokyo Metropolitan Library -

. Legends about Inokashira Benten 井の頭弁天 / 井ノ頭辨天池 .

川瀬巴水 Kawase Hasui

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

玉川上水を世界遺産に

- source : ngo-npo.net/tamagawaj/pc -

- quote -

Tama River 多磨川

Tama River flows from a source in 笠取山 Mt. Kasatori in Kōfu City, Yamanashi Prefecture.

The upper reaches of the river is known as 丹波川 Taba River, the middle reaches as 多摩川 Tama River,

and the lower reaches as 六郷川 Rokugō River.

Tama River was so famous that it was composed in an old poem as one of 六玉川 the six Tama Rivers.

- source : Tokyo Metropolitan Library -

..............................................................................................................................................

- quote -

... in 1590, Shogun Ieyasu Tokugawa created the Koishikawa canal which was sourced from the springwater in Inokashira, located higher in altitude than the central part of Edo. This had developed into the Kanda canal.

As Edo grew rapidly in scale, the increasing demand for water outstripped the capacity of the Kanda canal. Then, the Shogunate started to construct the Tamagawa canal, drawing water from the Tama River with rich water resource. The new 43 kilometers canal was dug only in seven months, and completed in 1653. Japan's constructing and engineering techniques were surprisingly sophisticated. The total length of the underground water pipes in Edo reached over 150 kilometers at the peak period, which made it one of the world's largest water network of the time in terms of service area and the number of beneficiaries.

The Tamagawa canal, with a stable supply of water throughout the year, contributed Edo to be a big city with a population of 1.2 million. More precisely, the reason why the canal could satisfy the water needs was the constant flow of water from the Tama River with fertile forests along with its upper reaches.

- source : JFS - Sustainability in EDO - Eisuke Ishikawa -

Inokashira 井の頭

The new waterway from the pond of Inokashira to Kanda was first supervised by

大久保藤五郎 主水 Okubo Togoro Monto. (? - 1617)

Togoro was a trusted retainer, who had been shot into the leg when protecting Tokugawa Ieyasu in battle.

Togoro had a good taste for food and water and was making sweets for Ieyasu, before being made the supervisor of the new waterway and well system in Edo.

Ieyasu gave him the name of Monto. 主水 ususlly reads "mondo", but Ieyasu changed it to make sure it refers to the importance of "clear water".

Monto's descendants proudly used this name as their nickname.

- reference : Okubo Togoro -

..............................................................................................................................................

- quote -

Waterways of Edo life

Only great engineering slaked the city's thirst

For centuries, the boastful citizens of Edo lorded it over country bumpkins by saying, “I’m an Edokko [native of Edo] ’cause I was cleaned with pipe water when I was born and I’ve grown up drinking pipe water ever since.”

It seems an odd thing to crow about given the cultural wealth of Edo, at the time the largest city in the world, but this pride in the city’s water system wasn’t misplaced. Cool, pure water carried by pipes to the city’s remotest corners was indeed a byword for the quality of life in Edo — as well as being the lifeblood of the city’s prosperity.

However,

coming up with an efficient and reliable water supply was no easy task. Much of Edo was built on land reclaimed from the shallow waters of Edo Bay, which — in the absence of the technology required to bore deep wells — only yielded brackish water. Meanwhile, Edo Castle and the samurai residences were mostly situated on uplands on the eastern edge of the Musashino Plateau. There, potable water was equally hard to come by because the friable top soil was not water-retentive. Indeed, the vast grasslands of Musashino had traditionally been ridiculed by Kyoto aristocrats, who lamented in poems that “Musashino has neither trees nor mountains behind which the moon can set.”

But when Ieyasu chose Edo

as the administrative center of his new fiefdom centered on the Kanto Plain, he was, of course, well aware of the water issue. In fact, on July 12, 1590, prior to his arrival at Edo on August 1, he dispatched his trusted retainer Okubo Togoro to investigate the local water supply.

Okubo dug a waterway in Edo

from Koishikawa (in present-day Bunkyo Ward) to satisfy the needs of the burgeoning new town growing up around Nihonbashi. By 1629, this rudimentary supply line had been expanded into the Kanda Canal, which channeled supplies from Inokashira Pond in present-day Mitaka into the Kanda River, then into a canal cut through the surrounding hillsides. After filling the ponds and streams in the elegant Korakuen Garden created by Lord Tokugawa of Mito, the canal water then entered the heart of the city along a wooden aqueduct across the Kanda River. Altogether, this system served the eastern sections of Edo, supplying about 25 percent of the total demand.

Being at first sparsely populated,

the city’s southwestern sections were sufficiently supplied with water from Tameike Pond. In the course of the city’s expansion, however, the pond kept shrinking until it was eventually incorporated into the outer moats of Edo Castle. It now survives only as the name of a subway station, Tameike-Sanno.

However,

as the population kept doubling and redoubling from about 200,000 in 1610 to more than 400,000 by 1640 and then to over a million — even possibly up to 1 1/2 million by the mid-18th century, had censuses included the daimyo households and samurai classes — the city was in need of a much larger water source. The answer was to be found in the Tama River, to the northwest of the city, where the senior shogunal official Lord Matsudaira Nobutsuna (1596-1662) commissioned two commoner brothers, Shoemon and Seiemon, to construct a system to carry the river’s water to Yotsuya, on the city’s northwestern perimeter.

The brothers accomplished the task

despite great hardships. In the new system, completed in 1653 and named the Tamagawa Canal, water was diverted from the river by a dam in the village of Hamura, from where it was channeled 43 km along an open canal to Yotsuya. From Yotsuya, water was guided into stone, wooden and bamboo pipes that crisscrossed the city underground. However, as the entire water flow depended on the force of gravity, the canal had to be precisely planned to slope only very gradually so that its Yotsuya outlet was high enough to allow water to flow out and down to every nook and cranny of the city.

This water not only quenched citizens’ thirst,

but also fed the trees and flowers that were planted all over, both in the samurai gardens and in poor commoners’ pots on sidewalks. Indeed, the abundance of trees and highly developed horticulture for which Edo was so admired by visiting Europeans in the 1850s and ’60s would have been notably absent without that water supply.

However,

the Tamagawa Canal also transformed Edo’s arid suburbs into fertile villages. A typical example is Nobidome in southern Saitama Prefecture. The notoriously dry grassland there (as nobi, meaning “wild fire,” implies) was part of the fiefdom of Lord Matsudaira, who was granted permission by the shogun to divert 30 percent of the canal’s water. Although the 25-km Nobidome Canal along which he channelled it took only 40 days to dig, it took three years to fill because the parched soil at first just soaked up water like a sponge.

When he died,

Lord Matsudaira was buried at Heirin-ji, the Matsudaira family temple that was moved to Nobidome. Nowadays, the large compound of the Zen temple is a verdant woodland designated as a natural monument — thanks to successful irrigation 350 years ago.

Though continually tapped in modern times,

the Tamagawa Canal finally went out of use in 1965 when it was replaced by the new Tone River system. Thereafter, the historic canal was abandoned by the authorities, except for its upper stretch in Hamura. Dried up and fast decaying, it then seemed fated to become yet another culvert in the Tokyo sprawl. Citizens, though, had not forgotten the fond memory of a rushing stream that once flowed fast past green banks. In 1986 local residents’ passionate, persistent calls for the preservation of Tamagawa Canal were finally answered when water was returned to the empty canal — albeit water recycled from a nearby treatment plant. With the return of the water, trees were resuscitated and birds and dragonflies returned to the 30-km stretch of the waterway that has evaded developers so far.

Finally, on May 16 this year,

the Tamagawa Canal won national designation as a historic site — a metropolitan designation it was accorded in 1999.

What was for so long essential to life in the city is now a welcome strip of green, a linear oasis in a concrete wasteland.

- source : Japan Times 2003 / Sumiko Enbutsu -

.......................................................................

- reference : Tamagawa Josui -

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

- - - - - H A I K U and S E N R Y U - - - - -

月かげや夜も水売る日本橋

tsukikage ya yoru mo mizu uru Nihonbashi

moonlight . . .

even at night water is sold

at Nihonbashi bridge

. Kobayashi Issa 小林一茶 .

Selling drinking water was a normal job in Edo.

And on the bright moonlit nights life in Edo just went on and on ...

(remember, this is a time without electricity )

..............................................................................................................................................

Matsuo Basho was working for the Water Office of Edo.

His home in Fukagawa was suited to supervise the Kanda waterway 神田上水.

. 芭蕉庵 Basho-An in Fukagawa .

. Basho working for the waterworks department of the Edo .

. Musashi no Kuni 武蔵国 Musashi Province / 武州 Bushu .

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

- - - To join me on facebook, click the image !

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

. Famous Places and Powerspots of Edo 江戸の名所 .

. Doing Business in Edo - 商売 - Introduction .

. shokunin 職人 craftsman, craftsmen, artisan, Handwerker .

. senryu, senryū 川柳 Senryu poems in Edo .

. densetsu 伝説 Japanese Legends - Introduction .

[ . BACK to DARUMA MUSEUM TOP . ]

[ . BACK to WORLDKIGO . TOP . ]

- - - - - ###tamagawajosui #tamagawawater #edodrinkingwater #idohori #mizubugyo #inokashira #waterways #botefuri #uzumaki - - - -

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::